Nancy Atakan’s solo exhibition A Community of Lines took place at Pi Artworks Istanbul, September-October 2017, a first-time collaboration between the artist and myself as the curator. Below is a written conversation between us that started a few weeks into the exhibition and ended in January 2018. It attempts to contextualize the exhibition within the wider frameworks of Nancy’s practice and those of the history and historiography of practical arts education of women in Turkey.

The production of Turkish crafts and needlework by women in the first half of the 20th century—while constituting a major area of political and ideological investment aimed to modernize the country—, remains understudied as such and has yet to enter the Museum. Working with memories of people alive today to bring into light particular histories of female lineage, the exhibition attempted to emphasize silence, the parts of our subjective histories that remain untold, which paradoxically constitute the stronger elements in the process of generational transmission. From there, silence, seen as the negative space left out by official lines of transmission, moves on to confirm / conform to the gaps and silences within historiography and museology.

Nancy’s works and research operate precisely within the space of this silence, moving between historic examples of needlework, photographic documentation, subjective accounts, and performative processes.

—Aslı Seven

Aslı: In our first meeting around your exhibition A Community of Lines, you mentioned a point of intersection between the traditions of stitching in the US and the traditions here in Turkey, and the role this practice had played in women’s liberation in both contexts. Following this first conversation, I looked into the sampling tradition in the US and went through the online collections of several museums. While prescribing women’s production within the domestic realm, sampler-making and needlework also provided a space of emancipation as one of the first fields of specialization, marking women’s entry into public life as professionals.

I would like to go back to this starting point for our conversation to ask about your relationship with needlework, how this point of intersection between the histories of your two countries operate through your own biography, and most importantly this insistence on genealogical context when it comes to women’s work. Female genealogy is also at the center of your exhibition, but operates quite differently as you relate women’s subjective accounts of their own lineage; the women in your exhibition attempt to write their own history instead of being catalogued from the outside. How did you arrive at this point of intersection and what was at stake here?

Nancy: I grew up in a small town in Virginia, a conservative state where state universities accepted only male students. After high school, I attended Mary Washington College, an all female college. Like the other institutions for women seeking a higher education in Virginia, my college founded in 1908 initially trained women to be teachers and homemakers only much later becoming liberal arts colleges offering humanities courses. Even television programs had helped to instil in the women of my generation the belief that the only professions proper for women were nursing, teaching, airline hostess, or secretarial work. When I came to live in Istanbul, women professionals following careers as lawyers, doctors, bankers, architects, and engineers surrounded me in my husband’s family. One of my works specifically, Father Knows Best (2011), a silkscreen series, refers to the difference I observed. While getting married may have been a priority for Istanbul women, it was not abnormal for a middle class Istanbul woman to study engineering.

The first work in which I used lace was the video Grandmother’s Lace. For this project, I visited and listened to the stories of elderly female family members. Since I inherited a trunk of beautiful lace work made by my mother-in-law’s mother, I was particularly interested to learn about their tradition of lace making. From these ladies (four who were actually born in Thessaloniki), I learned that the floral designs of the lace originated from abstractions of flowers that had grown in the gardens of family homes.

For one my first works using needlework, I thought of the historical importance handkerchiefs and made a series that I called Lingering Shadows (2015). Throughout my life I have always carefully organized and filed family photographs. I utilized computer-generated designs made from some family snapshots that have been digitally printed onto cloth and embellished with embroidery. I asked a retired teacher from the Olgunlaşma Institute* to help me produce these delicate handkerchief-sized objects. I realized that both handkerchiefs and needlework are only lingering memories in contemporary life.

As I worked on the Azade drawing series for the Sporting Chances (2016) exhibition, I realized that in Turkey women in the early Republic who were becoming professionals had only their fathers as role models. I became curious as to their mother’s stories. Who were the mothers? I decided to collect stories from the daughters of women who were born in the early Republic. As usual I began with the oldest women in my Turkish family. Women’s stories have not been written, but sometimes they have been passed on orally to the next generation. I wanted to know what the daughters remembered about their mothers. I wanted to capture some of their stories. I have collected some stories, but the collaboration between you and I came closest to capturing what I had in mind. Most women I interviewed, rather than talk about their mother’s or grandmother’s professions or education spoke about feelings. No doubt this also shows something important about female genealogy.

When I review works I have made to date, I notice that most deal with my Turkish family and very little with my American family. While it was not a totally conscious decision, I realize that the pieces in A Community of Lines bring together my past and present more strongly than any work I have previously made.

Aslı: You mention having organized and kept family photographs throughout your life. I think this personal archive has been one of the core materials feeding into many of your works. I am interested in your methodology in approaching these personal documents to put into question larger historical narratives, at times by creating very precise juxtapositions (as in the diptych What Something Is Depends on What It Is Not (2015), or Referencing and Silencing (2000)) and at others by using digital and transfer print techniques, alongside needlework. I would like to emphasize two aspects here: the movement between the personal and the historical aspects and the transition from photography as document to the deeply subjective renderings of needlework.

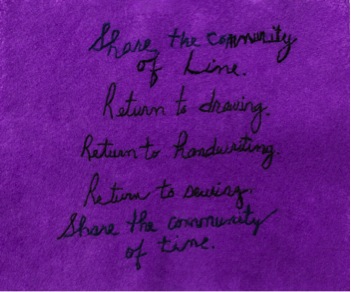

What emerges quite strongly in A Community of Lines is this highly personal, even bodily aspect of historical documents rendered in needlework. One individual’s stitching does not resemble another’s, it almost bears the mark of one’s body and breathing. I think this becomes apparent in some of the textual inscriptions on felt, such as When The Hand Tells Stories! or Return to Handwriting. Above all, the video Passing On II (2015), where a gymnastics routine is carried out by women from three different generations emphasize this bodily and subjective approach to memory. How do you negotiate this space between document and memory, fact and fiction, reproduction by print and the work of the hands or body-memory?

Nancy: This is a hard question for me to answer because I think I do it instinctively. Nothing is planned, it just happens. I do extensive research for most of my work, but I look for generalities more than specific details. I am not looking for proof of anything or that something is right or wrong. My master’s degree was in psychology and counselling and I did what could be called scientific research projects. I used statistics, made propositions and tried to prove their validity, but none of this made sense to me. I make art to try to understand and make sense of what I am living, observing, feeling, thinking, and experiencing. The intuitive way, that uses serendipity and follows a crooked path makes sense to me. It reveals complexity and layers rather than detail.

In my opinion, everything is subjective. What we observe, what we find in our research depends on our individual perspectives. Memory is selective and what may seem true at one point may seem completely wrong at another. A photograph is a document of a particular time, person, thing, place. We may look at it and recognize something. They freeze moments, but our memories are fluid. A date may be a fact, but almost everything else is fiction. When a teacher teaches with passion and knowledge, the student listens and takes something with them. In my opinion that feeling of excitement about a topic is important. If the teacher forgets a date or even remembers it a few years off, in my opinion, it doesn’t matter. Things need to be a bit off-center. Fiction conveys more and touches people’s cores in a way that facts cannot. Creating an atmosphere, conveying a feeling, seeing multiple possibilities, remembering, searching is what is important to me. I have never been interested in creating a recognizable style and wanted to be free to use whatever tool, material, or technique that I found important for a specific concept.

I have always been interested in the relationship between word and image. For the My Name is Azade project, rather than reproduce the photographs I found while researching her life, I decided to use the photographs as references for drawings. The drawings are not pages in a book. Each one tells its own story by itself. Handwriting rather than typed print seemed more appropriate for these drawings. As I said I am not interested in creating a recognizable style, perhaps it seems a contradiction that I am using my handwriting as an art object since everyone’s is different and can be traced to a specific person. But for this project it feels right. The handwritten story is more important than the drawings. Personal stories told with handwriting—thoughts taken from my personal notebooks; ideas I agreed with from texts I have read seemed to require handwriting, a more personal form of communication, a recognizably personal and very individual form. Sewing is slow, rhythmic and repetitive even meditative, perhaps like a dance. It allows the body more time and carves messages into one’s memory. Each letter is a challenge.

Aslı: Your research for this exhibition relied mostly on subjective accounts of people alive today and whom you interviewed on their memories of their mothers and grandmothers. This was a way to recover the history of a specific generation of women who came of age during the transition from the Ottoman Empire to modern Turkey. In our private conversations you often mentioned that instead of facts or critical thinking, most of the time what you got from these interviews were feelings. I think this underlines the importance we do not give to our own subjective experiences—what we deem unimportant or uninteresting in our own lives, as well as the lives of our parents is actually the most revealing in terms of contradictions that underpin women’s history and historiography in Turkey. The most compelling information is transmitted through the silences or gaps in life stories. This silence also translates into how we approach material culture.

To go back to the beginning of this conversation, much of the work done by these women at Institutes such as Olgunlasma was never deemed important enough to be part of public knowledge – even though in the 1930s state-sponsored exhibitions of practical art schools were common for a time, they were gradually abandoned and completely disappeared through the 1970s. This seems to represent today a missing link within the history of practical arts education in the early Republic years. You have actually previously attempted to open a dialogue around these works, with Granny Leyla’s Bedsheets from 1999 and Grandmother’s Lace from 2004, which was on view at the group show Trans ID at the Surp Yerrotutyun Church as we opened A Community of Lines. Could we trace a genealogy of this exhibition by looking into these works from 15-20 years ago?

Nancy: They can definitely be linked. In 1998 my mother-in-law passed away. I made these works around that time. While I had listened to her stories and kept many memories, I realized there were so many stories that died with her. Only a few of her friends and relatives remained and I believed I must collect a few more stories before it was too late. But, now I know I did not do enough. There are so many untold unrecorded stories, not just the stories of women from my family. The quality of the needlework I saw when I interviewed family members for my early work, surpassed anything I could imagine in skill, design, and sophistication. My generation was more interested in being modern, didn’t particularly want to use them, didn’t learn from their mothers to make needlework and put their grandmother’s and mother’s work into trunks. I used the pieces I inherited. I slept on bedsheets made by my husband’s grandmother, ate on table clothes she had sown. But, they were delicate and needed to be preserved and repaired. Over time lace in particular began to fall apart and finding someone to repair them became difficult. I bought acid free paper, wrapped them and I put many into a trunk. But, they should be in museums, not trunks.

Now, I am in Stockholm to collaborate with a Swedish artist and continue my research about needlework exploring transliteration and translation. Searching for similarities, perhaps searching for a common female language, yesterday we explored the Nordic Museum where there is a section for needlework. We looked at work from a specific time, the late 1800s and up until 1930. What struck my heart was to see women’s work valued and preserved, but still stored in glass file cabinets, another type of trunk, still classified under folk art, rather than framed and displayed on the walls of the museum equal in rank to oil paintings made by men. While I am here, the Swedish artist, Maria Andersson and I will make a wall panel out of fabric and needlework, a work we have named, Marking a Shift (2017), a wish, a proposal for a collaborative, cross-cultural inclusive non-hierarchic life style, respective of animal, plants and objects shared by everyone. We are looking to the past, the body movements shared by women performing gymnastics then and now, here and there. We are choreographing a story about our research and work together.

Aslı: Thinking about your collaboration with Maria Andersson, Marking a Shift, the word “activation” comes to mind: the activation of the historical material at the core of your research on Azade and the story of her father Selim Sirri Tarcan who brought Swedish gymnastics into Ottoman society and practice. Together with Maria you reenact the photographic documentation, trying to perform these movements, a transliteration of sorts. This process is then translated onto a collage of needlework that functions almost like a choreographic notation. I was intrigued by your decision to display this work along with its negative space, the carved out pieces of fabric, which I believe, carries something of the process into the work itself. Could you elaborate on this process in Stockholm, moving between historic examples of needlework, gymnastics reenactments and music?

Nancy: Maria and I started collaborating in 2012 when we discovered our shared interests in cultural transliteration and transcultural exchange. Our joint and individual research about Swedish Ling gymnastics as a modernist project in Sweden and Turkey has led to a series of separate works using our own modes of production. This work built several parallel narratives directly and loosely connected to Selim Sırrı (Tarcan), who brought Swedish Ling Gymnastics to Turkey during the Ottoman period and his daughters Selma Sırrı (Tarcan) and Azade Sırrı (Tarcan) who, influenced by their fathers radical ideas and ideals of a society, in the formative years of the Turkish Republic became pioneers of modern dance (Selma) and developed a therapeutic method of teaching gymnastics to everyone (Azade).

In October 2017, I spent three weeks at the NKF, the Nordic Art Association, in Stockholm sponsored by IASPIS. During this residency program, Maria and I produced two new video works: a back of the scenes video, Learning from the Past, Preparing for the Future (2017) and a performance video, Overlapping (2017); as well as a collaborative textile based piece, Many Unknown Things (2017). For our joint exhibition, we chose the title, Marking a Shift, because we researched a period in time when a major shift was taking place not only in Turkey, but also around the world. From Sweden, Selim Sırrı brought the music for the Youth March (Gençlik Marşı), Ling gymnastics, and impressions of a new life style back to the Ottoman Empire at the turn of the 20th century. With own 21st century sensibilities, we concentrated on this critical shifting time in the past, a period of hope and anticipation, wondering whether or not cross cultural collaborative work could help us better understand the ‘shift’ that is taking place today.

We made the video, Learning from the Past, Preparing for the Future, on the first day we worked together. We projected on the wall photographs of women taken from the Gymnastic Central Institute in Stockholm in the early 1900s as they performed Ling Gymnastics. We proceeded to teach each other the movements by analyzing the positions of the women in the old photographs. While we worked together and practiced the stances it was as if we were being taught by shadows.

Many Unknown Things is a collaborative textile based work that abstracted forms referencing Ling gymnastics, Azade and Selma Sırrı (Tarcan)’s gymnastic and dance movements, and examples of Turkish kilim and needlework designs. We visited the Nordic Textile Museum in Stockholm where we found several textile cross-cultural similarities and chose a color scheme based on antique fabric we saw there. The fabric wall panel is a thought track, choreography and a search for models for collaboration and sharing. Most of my three-week residency was spent making this textile wall piece. Choosing the color scheme and fabric even cutting out the shapes, ironing on backing, making duplicates took a great amount of physical effort, but it seemed we instinctively knew what we wanted. Quickly we had the colors, shapes, words and symbols but the real task was to choreograph our visual dance. It was a continuous trial and error process of pinning, sewing, looking, changing, and starting all over again. One night I decided one of the circles had to move over the edge of the background and finally the threads and figures and color combinations seemed to work, but we both thought something was missing. The night before the opening of our exhibition we felt totally frustrated. We went out, had a few glasses of wine, cleared our heads, got some fresh air, came back and started to dance as we moved outside the rectangle arranging onto the wall the negative pieces of cloth discarded on the floor around the studio. That was what was missing. We had stopped playing and had become too cerebral, too cramped. When we let our spirits fly everything fell into place and the project finished. We learned: That what is left outside is as important as that inside—the unsayable is as important as the sayable.

*Olgunlaşma Institutes were established in 1945 and there are still 12 functioning institutes in 11 cities. They offer a two-year training for girls who have graduated at least from primary school.

Linen, digital print, needlework, 37 x 37 cm.

Nancy Atakan, b. 1946. Her exhibitions include A Room of Our Own, Ark Kültür, Istanbul, Turkey (2017); Triebsand Online Exhibition Space, Volume #2, Zurich, Switzerland (2017); Unfold, Arte, Ankara, Turkey (2017); Whose Art History, Uniq Gallery, Istanbul, Turkey (2017); Letter from Istanbul, Pi Artworks London, UK (2017); Sporting Chances (solo), Pi Artworks London, UK (2016); Small Faces, Large Sizes, Elgiz Museum of Contemporary Art, Istanbul, Turkey (2015); Stay With Me, Weserburg Museum, Bremen, Germany (2015); 40 videos from 40 years of video art in Turkey, 25th Ankara International Film Festival, Goethe Institute, Turkey (2014); Me, Myself and I: ME as a Dilemma, Cer Modern, Ankara, Turkey (2013); Places of Memory-Fields of Vision, Contemporary Art Center, Thessaloniki, Greece (2012); Dream and Reality-Modern and Contemporary Women Artists from Turkey, Istanbul Modern, Turkey (2011) and Istanbul Next Wave, Akademie der Kunst, Berlin, Germany (2010).

Asli Seven is a curator and writer based between Istanbul and Paris. She is currently completing a practice based PhD at Ecole européenne supérieure de l’image in France, focusing on fieldwork and landscape practices as components of artistic research with an emphasis on collaboration. She has previously curated solo and group exhibitions at Pi Artworks, Arter, and Galerist in Istanbul. She is a member of AICA and a collaborator with ICI.