Artist Kiều-Anh Nguyễn speculates on how the air holds memory. She weaves through stories related to taste, scent, touch, and sight, moving through her childhood’s alleys in Hanoi, family feasts, and her grandmother’s deathbed. This text builds on her conversations with translator and editor wing chan and wing’s contribution to our series, “weather forecasting lake,” exploring her body as a weather station. wing’s voice comes back as a postscript after Kiều-Anh’s text, narrating an imaginary journey she took to the alley where Kiều-Anh’s grandmother lived.

This text is part of our ongoing series addresses artistic strategies to measure, report, fabulate, and tell stories about the weather, air flows, circulation, and other high to low pressure aspects of our practices and cities. Commissioned for the World Weather Network, a constellation of weather stations located across the world, and with the invitation of SAHA – Supporting Contemporary Art from Turkey, the series asks: how do artists respond to ideas of change, crisis, and future, focusing on various elements of the weather as an embodiment at the intersection of bodies, peoples, and landscapes? –Özge Ersoy

ventilation veins: the anatomy of air

Kiều-Anh Nguyễn

in the summer of that year, i tasted a spaghetti bolognese served with a smoked burrata at a fusion restaurant in hanoi. the burrata was as small as my fist–white, shiny, and hand-tied, resembling a belly button. as soon as the smoky soft cheese melted all over my tastebuds, it brought me to winters twenty years ago–to my grandma’s neighborhood.

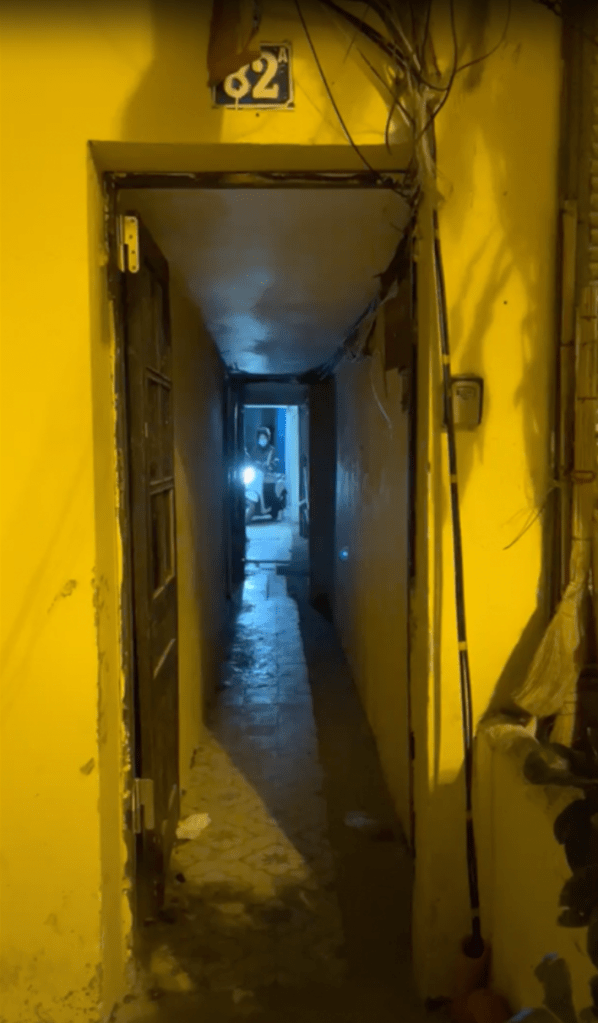

back then, hanoi’s urban planning was simple: the main streets looked like the midrib of a leaf, leading to numerous alleys interconnecting like veins, silently circulating life across a bigger living body. my grandma lived in a humble alley, like most of the retired railway workers who benefited from their union’s housing program. the neighborhood was rebuilt from scratch, following a bombing that ripped it through on a December night in the 70s.

she lived on a lane packed with tenement houses. they did their best to squeeze as many households as possible into the narrow street. they stretched the construction to the air above the old building and barely left enough space for breathing. even the air strapped itself in the humid stains on the walls. some have grown into a family of unique patterns of mold, or the unconcealable stale smell that one could recognize from the entrance of the alley. nevertheless, the skyline never exceeded the width of the street, sandwiched in between eyesights of tenement tops.

i wonder if my grandma’s skyline eyesight was the same when hiding at bomb shelters. she must have been composed of the thinnest air, disguising into whatever amidst the reality that she couldn’t see for herself.

or maybe there was no skyline for those eyesights below the ground.

can anything escape a memory tube, or will it forever circulate in between where the sky and the land mimic and reflect each other?

as long as air can squeeze itself within, it holds it.

air holds memory.

the notion of belonging, along with the responsibilities it carries, grows in me as the ceremonial smoke grows thicker by time. those are the lessons from a parallel world that you only enter on the occasion of celebrations, wrapping up a period of time by carefully unwrapping memories with rituals. every year, lingering somewhere between winter and springtime of the lunar calendar, my grandma’s alley served as the main ventilation vein. the street was layered in a cloudy scented atmosphere: of warm food streams, the pale humidity of spring, and the ashy remains of burning matters.

in preparation for rituals, one cleans the altar with warm ginger water, and people can talk to their ancestors only if they light up three sticks of incense. there is something humbly graceful in these movements: subtle, yet definitive. the thin, crispy joss sticks might crack any time, yet flicking off the flame right when the little tips glow in red can be tricky. those magic wands then transform its physicality into thick air, lacing sentiments between the living and the long-gone-yet-never-forgotten. flowing smoke would slowly leave traces of sweet brown clouds on the low attic ceiling that keeps track of sheltered wishes and prayers we sent to the other world. a receipt after years of scentless oud. an ode for the past from the present.

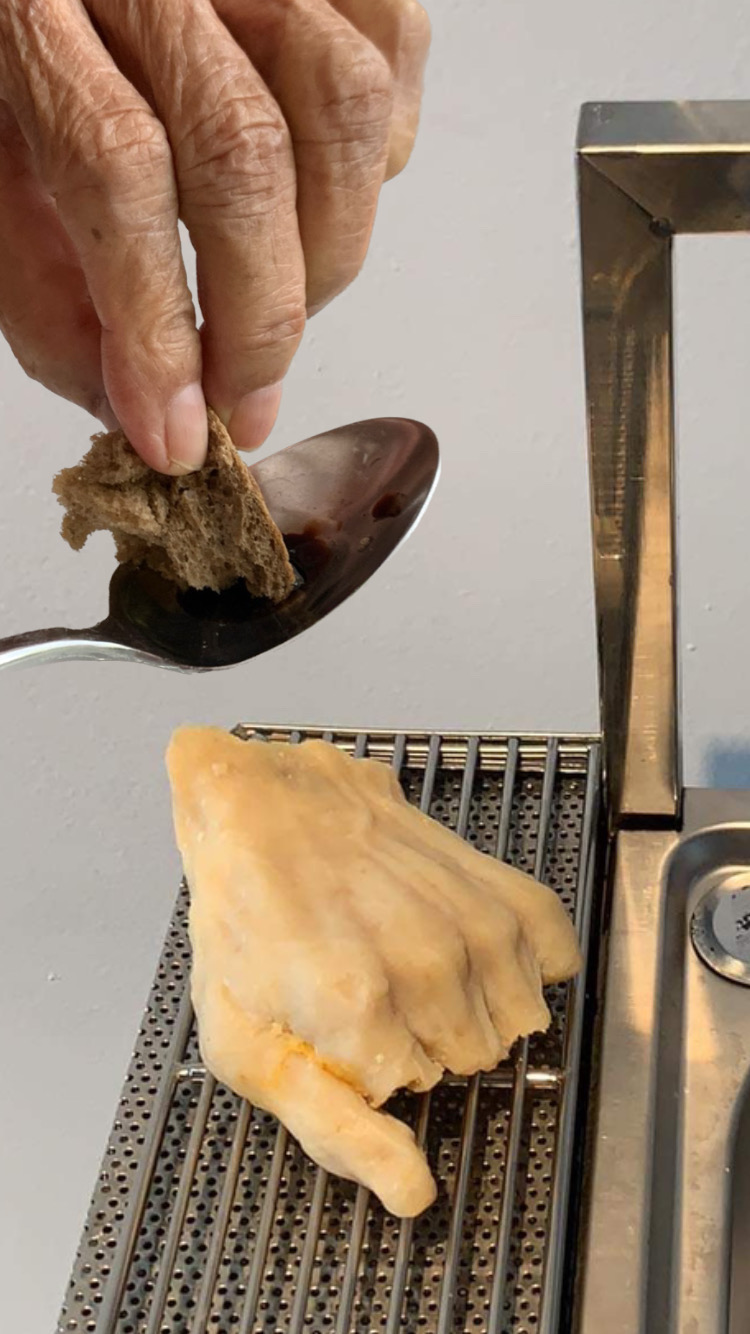

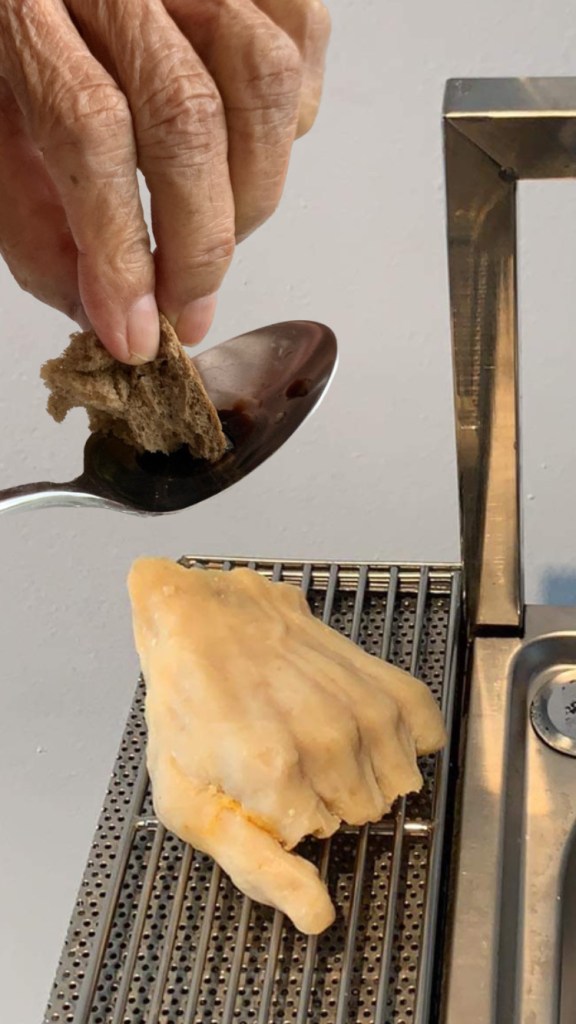

after incenses are dusted, food is reheated for family feasts, while paper-mache models go to the open fire. the warmth of the reheated food gradually feeds us with ideas of home. steams as warm as skin, weaving from one home to another, from a year to another, until the smell of festive dishes grows like a childhood blanket that one still keeps. we also share life updates through paper-mache-to-burn models, as detailed as desired: a never-released iphone model, a pfizer covid shot, hand-sewn gucci ballet flats made of paper, a 10-story house. funny how I have never seen anyone trying to burn a map. do dead people ever forget about the familiar routes no matter how the future alternates?

we watch adults, sprinting alcohol on the thin skin of colored paper. a wet piece of paper is now a bait for an open fire.

votive smoke evolves from the ground, bitter, from the plastic and coloured bits, stingy, spicy. in the midst of adieu offerings, paper vehicles and houses fall down, shiny gold pleats disappear in the fire. dark clouds emerge from thin papers into thick airy paste of dust, slowly moving to the ventilating veins and sending off a year worth of memory and another eternity of remembrance.

i remember running laps in the neighborhood, trying to hide in shortcuts or even tinier alleys as a child, just to find myself end up in the main road where the rusty railways cross by. they say that fire is the portal to the unknown. and then everything evaporates to other unseen worlds, slowly joining the tracks riding toward the new year. though not seen by the eyes of mundane people, no matter how hard I sneak into the shortcuts of reality, my childhood as well as my grandmother’s, found me through a bite of an unacquainted taste. as if my body is a vessel of memories, where nothing can escape a closed system of circulation.

as if the ventilation vein never leaves my being.

evaporative lake and untraced park-ing lots

i touched my grandma’s forehead, gently, as an act of care for a person who can’t function physically. the only remaining consciousness was the softness of external contacts.

she had come out of a coma, just to find out that she was still alive.

grandma’s house was cocooned in an alleyway nearby a park, next to a lake. on weekends, all of her grandchildren reunited for an obligatory grandma visit and a spatial floating around.

we all believed that the lake had a superpower–that it turned people into evaporated beings that could only be seen in another realm. once, when we were walking past the lake, the crowd was looking for “a woman in her sixties who went missing in the morning. she was “last seen at the lake, carrying an unsolved debt.” couple of steps away, we thought we saw a naked man in his twenties, rising from the lake, and quickly dissolving into thin air. later that day, he made an appearance on the bulletins. emergency personnel found him, naked, unalive. next time we went to the park, a disaster happened.

i thought i was familiar enough with the route for things not to go south: my little scooter’s wheels slide into the surface texture, letting me know when to speed up, swing my arms, jump over a bump, or at which turning point i have to pretend that i’m exercising to avoid receiving undue attention from the park rangers. everything had to be precise to fit and sling between thin strips of pavements and other unpredictable factors. perhaps, vibrations and momentums have been transmitted through my skin into the deep tissues, stimulating a type of muscle memory: this muscle memory does not necessarily perform anything but has memorized the feeling of safety. a kind of comfort zone. yet, there was a path just before crossing the road—a flat, shining, new concrete, poured only a few days ago. that physical extension waited for an unknown velocity and untrained muscle memories to discover things we are not even aware of. my then-four-year-old brother slipped at that particular spot in the lake before we realized he was drowning. luckily, some old swimmers saved him; he didn’t disappear.

grandma got cancer from years of breathing in brown oudless rings that clouded both the low gypsum sky above the altar and her lungs. her voice was spongy as a wounded trunk of agarwood, with breaths replacing words, whispering like wind blows. instead of resins or oud, there were ponds of fluid, leaking, as the air ventilated. maybe she had to sleep with her mouth open so the little pools can continue evaporating when the sun came down.

after waking up from the seemingly endless coma void, morning dews conceived into late drops of tears, barely carrying the weight of lightness and being. they stayed at her dry eye sockets and never made it to the other part of grieving on her face or her shaking body.

the largest organ of her body, her skin, turned into an autonomous picturesque diary. ridges were filled with waterless channels, mountain slopes in the slices of whorls and arches on her fingertips. grandma was now covered by a scratch map of glossaries for faded and tainted landmarks she had never stepped foot onto.

how do you call a leaf with only its skeleton, i asked google. i remember that people used to skin out bodhi leaves to reveal an ultimate fragile anatomy, milky white (barely bearing any force holding life), almost unrecognizable to a degree of holiness (maybe from the lifelessness chastity it holds), and they would humbly put it next to the buddha statue on the altar. the green flesh that used to generate liveliness didn’t matter anymore, but a generic shape recording what once held everything together—a mere silhouette, was now being treasured. how do you value what is more important: the livelihood of being or the stillness of existence?

do muscles hold memories of ethereal body pleasures?

do they remember the pleasure of moving, of being moved?

do they carry the energy and force in exchange in between touches?

does my muscle memory ever forget my grandma’s forehead texture where my fingers practised goodnight gestures as running tracks, or they will only collect the miles running but the joy of tiptoeing on her dry forehead veins is freshly generated every time?

does muscle memory ever recall the reasoning behind our movements? for instance: my grandma’s mission was finding paths and guiding us through our childhood, one weekend walk at a time. she guided us through art lessons and taught us how to skip park tickets and how to find peace as well as discipline in sunday prayers and blessings from buddha. will any of her stroll remind her to continue such guiding duty, even after her grandchildren are all grown up and flying away like flocks of birds?

though immobilized on her deathbed, my grandma’s muscles routinely went for a mental afternoon walk to the park (which is now partially a parking lot) and the neighborhood. how do i know it? she still practiced counting each remarkable playdate of ours, including the drowning incident. eventually, her forgetting curve slowly tilted as she was tracing ghosts of old paths. maybe her muscle memory is now gone and probably drained while tracing a memory that has been replaced with no further updated data.

not too long after, in one of her last strolling dreams, grandma finally took a rest by the lake, behind the pagoda where she used to spend her weekends praying for peace.

maybe she figured that paths are replaced in the parks and the lake turns everything into evaporated beings, still.

//

Postscript

wing chan

Seamus Heaney composed a graceful poem called Postscript, first published in The Irish Times in 1996. Full of signs and imageries of life, the scenery in the poem arrives fast. Reading it you know his pen moved fast, too. Life and death are hard to articulate; traces of life and death are comforting to name.

Kiều-Anh’s Ventilation Veins is grounded in a profusion of traces or, more precisely, a sequence of material things in Kham Thien Street that signifies labour and loss. The sentences move fast, overcoming the heaviness of the subject and the abstraction of the landscape. They leave you with a sensation of having been there. In Evaporative Lake, conversely, the air is thick. When her subjective ‘I’ decided to physically reach out to her grandma’s dying body and walk in the neighbourhood, the time does not pass, her feet drag, and the story drifts. The narrative turns misty and eventually muted. I sensed there was a compulsion and an inability for her to directly address the events and emotions. Her art practice, as I understood it, is to find physical forms for her memory, leveraging a capacity to mark sites and people with complex layers of scents. The translation from senses that are felt to words on a page remains a challenge. But who is afraid of seeking ways?

It is in noticing this possible negotiation between experience and narrative that I travel to Vietnam through memory. Indeed, Heaney too composed Postscript from remembering a journey along the south coast of Galway Bay while writing his lecture notes at home. Dust occupies my first Hanoi evenings. I remember it as a hazy city. Locals naughtily added winking eyelashes to its name, as in Hà Nội, attempting to shake off the dust in the air. The signs that are constitutive of the ‘ventilation veins’–railways, alleyways, bomb shelters, ruins, mould, stains, odour, scents, smoke, ash, and fire– are condensed in this one picture in yellow and blue hues. I know that once I have said it, your eyes cannot un-see. That is the power of a narrative. The dim tracks casted by the shadow, the cracks on the walls, the expressive, unfinished paints on the doorframe, the faults in the floor tiles and even the diffusion of that light source at the opposite end of the pathway all contribute to a viewing experience that mourns the passings. Unlike the devastating scene in Kham Thien Street during the war in December 1972, the concrete architecture in this picture refuses to collapse despite signs of wear. Here, the architecture is an object that carries contradictions and a metaphor for withstanding extreme socio-political climate, weather changes, and force of circumstance.

Kiều-Anh Nguyễn is an art practitioner based in Hanoi, Vietnam. Since 2020, her research-based art practice foregrounds olfaction to explore memory tracing, nature, and practice of care. Her art takes forms of soft sculpture, writing, drawing, and food experiments with a vision to cherish the ephemerality of life, including unnoticed details and unconventional narratives.

wing chan works at Afterall and likes Thursdays.