Translating and reproducing Füsun Onur’s response to Cengiz Çekil’s work in 1976 is instrumental for m-est.org. Onur takes on historicizing and contextualizing her colleague’s work and uses the article to criticize how critics approach art work. This shows a concern for the ecosystem in which she produces as well as an agency with which she participates and heralds the vocabulary that is to be employed in writing about art. Thinking about art criticism in the age of Yelp, Onur’s response interrogates how we choose to write about work, be it our own or others’ and what we expect from the audiences and producers that we address.

—Merve Ünsal

The Critic’s Approach

by Füsun Onur

Included in the third exhibition of sculpture and ceramics in the gardens of the Archeology museums was a work that should have been striking for us. This was the work by Cengiz Çekil. Not only was this work not referred to in the articles written on the exhibition, even with one sentence, the name, Cengiz Çekil, was not in the list of participants. I waited until today—this was a work that should not have escaped our attention.

Critics think that they benefit viewers by placing works randomly in art movements. Their irresponsible, effortless, arbitrary habit of appreciation or lack thereof does not benefit the viewers. In fact, critics have the opportunity to be enlightened at the moment that they pause, by establishing a relationship with the artist; they should make this mandatory for themselves. To focus on form and movement misguides both the training artist and the viewers into formalism and nothing more. This would be the biggest mistake committed by educators who train artists and the critics. The aim is to guide the viewer on how to look at the work, to help them understand and to love it. Without such an approach, the example of Cengiz’s work, passes by without a new form of narrative, without leaving a trace, not being able to be evaluated.

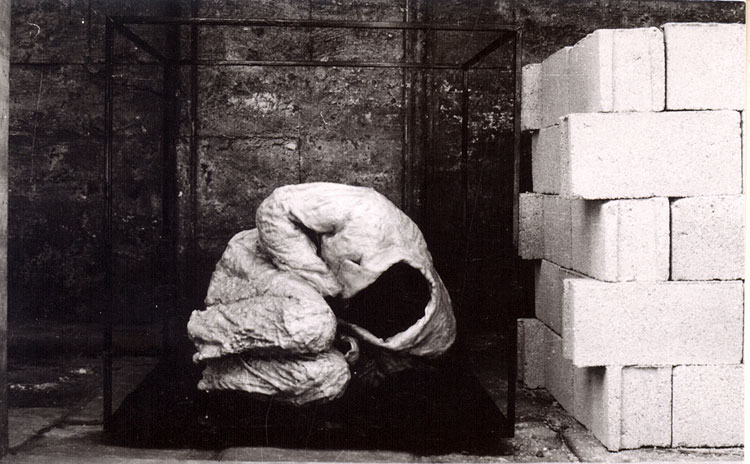

Let’s get to Cengiz’s work. The title is: Embryo/Crust – Resistance/Energy. It is an art work. In a cube formed by iron rods, a person made of polyster is placed in the embryonic position. The person’s position is revealed to us through the clothes; the polyster cast is empty inside. Right next to it is a tomb, constructed from one meter-long briquets. The floor of the tomb is made of soil, and through the soil, a resistance line passes—when electricity is provided, the resistance becomes red.

The statement is foregrounded in this work. And the name is a mathematical equation. It warns the viewer, evokes thinking. It is a name that includes the absolute symbols in mathematics. First, it makes the viewer sweat the way a student of mathematics sweats with effort. It seems as if the equation is not solvable. With the curiosity o the unknown, the viewer is hooked. Realizing the generalness of the symbol, the viewer understands that the equation is a form in and of itself. He/she finds the real concept provided by the formula. Through symbols, the work reaches the highest level of transparency that can only be achieved through language. For example, in math x symbolizes this and y symbolizes that. The experiment does not yield results. Then, x is not this and y is not that, they are variables. Cengiz finds this balance with his work and leaves the definition to the viewer. The essence of the work, in most general terms is this: opposite concepts such as death, birth, energy, resistance, the resistance of the battered when vanishing, replacing the new, the emergence of new values and the constant progress as with everything else, is the same in art. This is the narrowest meaning of the work. The viewer can develop it in their mind in any way they want, they can complete it. In order to say this, the artist has used the most effective language; it is fertile and flexible. The approach to the work is enabled with simple materials such as iron, soil, briquets, resistance and thus constructs an archaeological language. Cengiz defends the path that he has taken through participating in the exhibition with such a work.

The way to approach a work is not through placing it in a movement, a form. The critics remain on the surface as such, not able to escape clichés. A critic who understands a work first relays their thoughts and refers to the movement that the work is a part of, addressing both the opposing and shared dimensions or the novelties that the work brings up. But what the critic should know foremost is the alphabet of plastics. They should know it so that they can teach viewers from all ages how to enjoy a work. A critic has defined a work in the same exhibition (my work) as pop even though it is not pop. To keep in mind the name of a movement does not go beyond pedantry and I don’t think can be a beacon. Before movements, formalism, the vocabulary of plastic arts needs to be in the reading. For example, the work defined as pop by the critic constitutes of the repetition of three elements (an anthropomorphized column) with intervals, silences in between and the fourth ends with an explosion. The fourth is the transformed, opened up, flowered version of the first three. It carries the symbolizing of a place worth paying attention to, a weaving of decoration and evoking a moment as a function. I’m not going to go into details as this is not the work in question.

My doubt is about the critics who lack the general concepts of plastic arts. These concepts ceaselessly develop and expand from yesterday to today. We have no time to lose. If this was not the case, would Cengiz’s work in the gardens of the archaeology museums be overlooked?

Translated from Turkish by Merve Ünsal

Füsun Onur was born in Istanbul in 1938. Following her studies at the Department of Sculpture, Istanbul State Academy of Fine Arts, she continued her education in the USA with a Fulbright scholarship. Her work has been shown in solo and group exhibitions at Istanbul Modern (2011), Augarten Contemporary, Vienna (2010), the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (2005), ZKM, Karlsruhe (2004), and the Kunsthalle Baden-Baden (2001). She has participated in dOCUMENTA(13), the Istanbul Biennial (2011, 1999, 1995, 1987) and the Moscow Biennale (2007).

Born in 1945, Cengiz Çekil grew up in Bor, in Central Turkey. He received his BFA from Gazi Institute of Education in Ankara, and went on to study at École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. There he held his first solo exhibition “Réorganisation pour une Exposition”, in the basement of a café in 1975. He returned to Turkey in 1976 and received an MFA in Sculpture from Ege University in Izmir. His first solo exhibition at Rampa was held between May-July 2010. Curated by Vasıf Kortun, the project comprised works produced between 1974 and 2010. Çekil participated in noteworthy exhibitions such as “NEWTOPIA: The State of Human Rights”, Mechelen, Belgium (2012); I m Still Alive: Politics and Everyday Life in Contemporary Drawing” MoMA, NY, USA (2011); “What Keeps Mankind Alive?”, 11th International Istanbul Biennial, Istanbul, Turkey (2009); “…With All Due Intent”, Manifesta 5, San Sebastian, Spain (2004); “Orient-ation”, 4th International Istanbul Biennial, Istanbul, Turkey (1995); State Museum of Painting and Sculpture, Ankara, Turkey (1967). Çekil lives and works in Istanbul.