Politique Culinaire is an open collective of artists, amateur chefs, writers, and researchers that investigates historical menus and their setting with the aim of affirming the political dimension of the culinary. Its members are Franziska Pierwoss, Sandra Teitge, Max Benkendorff, and Albrecht Pischel.

Below is a dialogue between Franziska Pierwoss & Sandra Teitge and Merve Ünsal, following Pierwoss and Teitge’s presentation at Maskan Apartment Project, Beirut, on January 28, 2015. Maskan Apartment Project is a curatorial project initiated and organized by Mirna Bamieh.

Merve Ünsal: Politique Culinaire is a collective effort that works with situations and setups, both geographically and institutionally. Could you elaborate on your working methodology and the decision-making when, let’s say, you receive an invitation?

Merve Ünsal: Politique Culinaire is a collective effort that works with situations and setups, both geographically and institutionally. Could you elaborate on your working methodology and the decision-making when, let’s say, you receive an invitation?

Franziska Pierwoss: The initial idea of Politique Culinaire (PC), a collective consisting of four members, two artists and two writers-curators, was to look at political events by focusing on the complimentary banquets that accompany any political event or historical decision-making process. Briefly: to focus on the role of food in politics and vice versa. We assume that this particular set-up allows for encounters and conversations outside of the classic conference room setting. The nature of the project is to be defined anew from case to case according to location, city and political event or question we look at.

Sandra Teitge: We started to work in a collective only in the spring of 2014 and in connection to a project in the framework of the performative conference Appropriations organized by Florian Malzacher at the Ethnological Museum in Berlin. The idea to focus on the Berlin Africa Conference developed out of conversations with the curator. 2014/2015 is the 130th anniversary of the conference and we wanted to address the impact of this seminal event, especially with regards to the institutional setting of the museum, in which the whole project took place.

In the center of Berlin the former Palace of the Prussian royalty is being rebuilt. It is a very controversial project that is predominantly supported by conservative reactionaries with strong ties to the political and entrepreneurial landscape of Germany. The new architectural complex is called Humboldt Forum and will eventually house the collections of the Ethnological Museum and the Museum for Asian Art, at present both in Berlin-Dahlem. In order to maximize the enormous potential presented by the relocation of the Dahlem-based museums to the reconstructed Berlin Palace, the Humboldt Lab Dahlem was set up by the German Federal Cultural Foundation and the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. Appropriations was part of a series of curatorial suggestions in the framework of the Humboldt Lab Dahlem.

This was a particularly complex situation that involved many different parties. Since the four of us are not in the same location (three in between Berlin and Thailand and Lebanon, one in Minneapolis/St. Paul), the project developed via numerous hour-long Skype conversations. We always try to find a consensus for every decision we take. And since the four of us reveal very different viewpoints and backgrounds, this process often takes multiple discussions before we come to a mutual decision. And sometimes it is not mutual, but majority-based. Our composition reflects a healthy balance on many different layers: two women & two men, two artists & two writers/curators, two East Germans & two West Germans. So far, this diversity has been very fruitful and productive.

For future projects we will not always work in this constellation. We consider the collective fluid and adaptable to different situations. For Beirut, for example, only two of us, the two women, conducted the initial research. We are in the process of developing a more precise proposal at the moment, which also involves deciding if and to what extent all the members will be involved. Some of us are generally more interested in the theoretical capacity of the project, such as publications, whereas others would like to travel with the project to different places and organize culinary events in situ. I, for example, have been hosting discursive dinners with my initiative “Dinner Exchange” and Franziska, on the other hand, has been using food as a medium in her performance practice since her studies.

Basically, we re-position and re-adjust ourselves with every invitation and take time and site-specific decisions, which work for every collective member in this particular moment.

MÜ: The relationship that you build between the physical setup of an important dinner and the issues discussed during that dinner is satirical and critically engaged. What do you think the function of reenactment is, within your framework?

ST: We have had heated discussions surrounding the term reenactment. For a moment, we liked the term re-dedication but then switched back to reenactment because it comes with a certain history (in the art context) and connotation that we felt functions well for our purposes.

In our practice we–only–reenact the culinary element of a historical situation. In that sense, it is not a reenactment in the true meaning of the word. We believe in the power of food and culinary gatherings. The physical activity of digesting is also interesting when thinking about the notion of dealing with (literally digesting) certain historical events or facts that might have been neglected or forgotten about, possible blind spots of a society. Our guests have no choice but to re-chew and to re-digest topics and issues that might be uncomfortable via food that might feel uncomfortable for our contemporary stomachs. A culinary menu always reflects the socio-political realities, attitudes, and fashions of its times. By re-cooking or re-enacting a historical menu, we force their stomachs to deal with unfamiliar food… and eventually, hopefully to deal with unacknowledged, possibly suppressed, elements of History. But it will not always be so somber and serious. We are planning on focusing on more contemporary, slightly lighter, situations in the future.

FP: In the dinner planned around the Berlin Africa Conference we tried to create an engaged conversation by raising certain questions through short table speeches by special guests like an expert for international law, or a young representative of an African internet start-up. At the same time, we planned to have a very curated seating arrangement, in which invited guests take a key position between other guests in order to encourage what Max liked to call “conversation clusters.” We are very concerned with opening up a space for conversation that is not pre-defined or directed but rather encourages an engaged confrontation of important questions.

MÜ: As a gesture and as a framework, how does food serve you within the discourses that you are seeking to build? What do you think is the potentiality of creating a social situation that mimics and works off previous “social” situations?

FP: We believe that the set-up during a complimentary banquet offers guests, politicians, and speakers an important social space that significantly differs from the conventional conference room. Every guest is happy to break the routine of potentially tiring discussions in order to dedicate a moment to enjoy his/her food. Simultaneously, the table situation allows for a more personal and less formal discussion.

As we learned from conversations with chefs serving statesmen and diplomats, the reality of those dinners might not be as exciting as we like to believe. Protocol suggests small talk around such tables, which follows common rules of international politeness and general themes such as family, sports, etc., or participating parties use the situation at the table to rest and to nap a little. But at the same time such dinners also play a symbolically charged role in certain circumstances whereas food is only served as a backdrop for the real talk.

Furthermore food does create a significantly different atmosphere for encounters to take place. It deals with aspects of hospitality, the notion of the guest, seduction and pleasure. Pairing that material with often critical and ambiguous political subjects creates a tension that we aim for in order to create a discussion and conversation that leaves the framework of the ordinary.

The next aspect is the immediate response food claims. Does the participant of the evening by refusing the food decide not to take part? To what extent can you regard food as being political? Do you participate once you take it in? Do you abstain by not eating the same dishes as were consumed in a particular historical situation? All these questions do matter to our discussion. Food has always been a representation of class, time, and power.

Interestingly enough, it was a problem for the hosting institution that we were using public funds to serve luxury dishes to discuss Germany’s involvement in colonial history, as if it were a subject that would adequately be represented by less exquisite food due to the serious nature of the subject.

I would be careful to claim that we mimic a previous social set-up. I think we refer to it by serving the same food. But apart from that the reference to the actual situation is interpreted very freely and in different ways. Our intention is not to play statesmen at the same table. It is about creating a set-up via the use of food that allows a re-staging of questions and discussions that we feel are necessary and relevant. Usually, only very few people have access to be present at such meals; of course this is a protocol we mimic but we open it up for a different use in our interpretation.

We really understand the table as space for a potential dialogue that can only take place now, after time has gone by, and for conversations that previously have been impossible. It is like putting a magnifying glass on a historical situation since most events in historical decision-making are shaped by personal behavior, a current state of mind, etc., even the ones that happened six months ago.

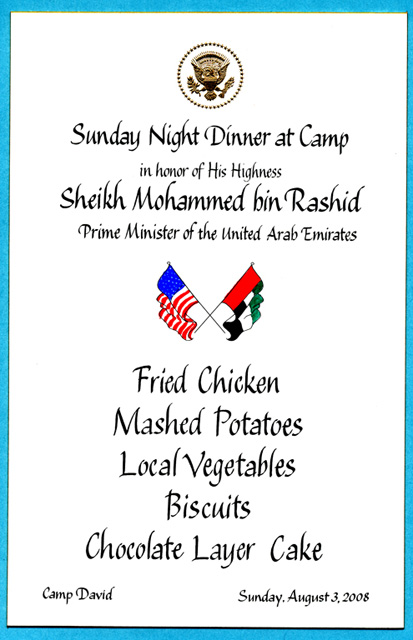

Does fried chicken possibly encourage you to achieve a peace agreement?

MÜ: How do you situate your practice within the art historical—by now—canon of relational aesthetics? There is also the social/performative/ephemeral elements of Fluxus in your practice. What is your relationship with these art movements?

ST: Personally, I am not a strong believer in relational aesthetics so I would not want to associate myself with this canon. I prefer the connection to Fluxus, which actually succeeded in stepping outside of the realm of Art. It is very important to us to include and reach an audience and participants other than artists and curators. The art world can be very self-referential and disconnected from the actual socio-political reality, which constitutes a point of departure for our practice as Politique Culinaire. So we are in a way obliged to extent our invitation to protagonists in various fields besides art.

All of the elements mentioned by you –social/performative/ephemeral– are important notions for us in our practice and we are always re-inventing ourselves and our actions for each new situation and framework.

FP: I personally do get bored fairly quickly by exhibiting an overly artificial situation or social set-up reproduced solely for the art context. It stays as an exhibit, which is not a bad thing but maybe not within my interest. PC tries to create a space for certain social situations to build up and unfold and very possibly take their own direction outside of our limits of control. The fact that there is no planned or fully staged set-up is important in order not to play or stage a situation, but to open up for potential encounter, discussion and disagreement. And Politique Culinaire is not limited to the art world only, we would be happy to stage these situations in many different contexts.

MÜ: What do you feel about “claiming” a social situation as an art work? What do you think this does to the audience who are consumers/participants/viewers all at the same time?

FP: I do not think that consuming any kind of art, either visual arts, theatre or dance ever is a non-social situation. From watching the Mona Lisa together with 135 other tourists to following a one-to-one performance in a white cube is predominantly a social experience. Therefore I would rather use the term “consciously creating” a social situation rather than claiming one. Not that I mind the notion of claiming, but if I would use claim, I would assume the situation to be a preexisting set-up hijacked and transferred to the art context. Our aim is to create a new situation inspired by the routines of a formal social situation such as a state dinner in a different context (that does not have to be a exhibition space at all as mentioned above) and then let it unfold itself.

As there is no social situation that does not involve hierarchy, divisions, actors, and viewers. I truly believe it is important never to underestimate the audience. And I understand the people part of our dinner situations as confident participants and consumers and viewers at the same time. Whereas the set up we create implicitly demands a rather active position it still remains the choice of the guest to where she/he would like to take that.

MÜ: What is next? Or rather, what is your dream dinner or lunch to reenact and where would it take place?

ST: We are currently still in dialogue with the Humboldt Lab at the Ethnologische Museum, where we were supposed to have the Berlin Africa Conference dinner. We would love to organize it elsewhere as everything was prepared and organized. We had a fantastic guest list, the best chef-in-town etc. Especially with all the discussions surrounding the Humboldt Forum it would be a productive critical addition to the existing discourse around the future Berlin Palace and its programming.

Besides the Berlin context, we have numerous ideas of dream dinners and different formats. It is simply a matter of focusing on one, gathering the necessary means, finding the right location etc.

We are open for business.

*Update: After this interview was conducted, Politique Culinaire was informed by the Ethnological Museum Berlin that the dinner of the Berlin Africa Conference would not take place in collaboration with the institution.

Franziska Pierwoss was born in 1981 in Tübingen, and grew up between Germany and Swaziland. Currently she lives in Berlin. Pierwoss is a performance and installation artist, who also works as an organizer & initiator of various cultural projects. She graduated from the Academy of Visual Arts in Leipzig, Germany. With a strong focus on durational performance and collaborative practices, she develops site specific installations. Her works create situations of engagement in which personal and political boundaries are called into question.

Sandra Teitge (*1982, East Berlin) is an independent curator, writer, and researcher and artistic director of the residency program FD13 in Saint Paul, MN, and co-founder of the food organization Dinner Exchange Berlin Americana. She organizes discursive events and exhibitions in the realm of contemporary art that often involve a culinary element and is interested in creating time-based situations, which focus on dialogue, knowledge exchange, and the body. Recent projects include the WorldWide Storefront project organized by the Storefront for Art & Architecture New York, and the Pavilion of Georgia at the 55th Biennale di Venezia. Previously, Sandra worked in the artistic office of the 7th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art.