Conversation: Nancy Atakan with Tuğba Esen

Nancy Atakan’s monograph Passing On, edited by Nat Muller, has been recently published by Kehrer Publishers, Germany. The book looks at Atakan’s production inspired by the past, memories, social transitions, and female role models. Below is a conversation with Nancy Atakan on her book Passing On, effects of female role models on her life and art, and the shape her work has taken throughout the years.—T.E.

Tuğba: “Passing on” had already been one of the main concepts you adopted in your practice. When we look at the series included in the book, do we see continuity with your earlier production and thoughts?

Nancy: I have a large body of work because I work continuously. Some have never been exhibited. I deal with what I am living at a specific time. But, I can say that as a concept, “passing on” can be traced through my earliest to my most recent art practice. As women and as artists we continually pass on stories, ideas, as well as objects to the next generation. Whether we are aware or not aware; whether good or bad, we are always handing something down.

I like story-telling and women have always been the storytellers of family history. Some women who influenced my life passed something on to me. Perhaps I too am passing something on to others.

As professional women we need female role models. Painting has always been a technique used by male artists. While painting, I searched for female painters and at one time looked at Helen Frankenthaler’s technique and studied Leyla Gamsız’s use of colour. As I researched for my doctorate thesis, I realized that conceptual art was also male dominated. In the 1960s and 1970s women artists working in western cities who stressed concept over perception and idea over morphology were not classified as conceptual artists. Like male conceptual artists, many female artists rejected modernism, but they argued not only against its aesthetical base, but also against its gender politics. Like them I saw that painting and sculpture could not be separated from a masculine rhetoric. I shared their use of collaboration as a major strategy and used female crafts such as needlework and lace. I also wanted to reclaim lived experiences and everyday gestures, my own body, and how it was to be represented.

Tuğba: Could we speak about the feministic approach in your work? Where does the My Name is Azade (Freedom) series stand within this practice?

Nancy: Inspired by Luce Irigaray’s writings, I made an artwork in 2003 that was exhibited at Pi Artworks. Her writings reinforced my belief that we need strong female role models and I made the big pink neon sign, Why not two gods? I am asking, who are our important female role models? Where are our pink goddesses? How can we function in society, how can we build our lives without them? I am a woman and I deal with experiences that affect my way of existing in the world as a woman. Male painters depicted women, painted their bodies. I decided to use my own body and voice in my work.

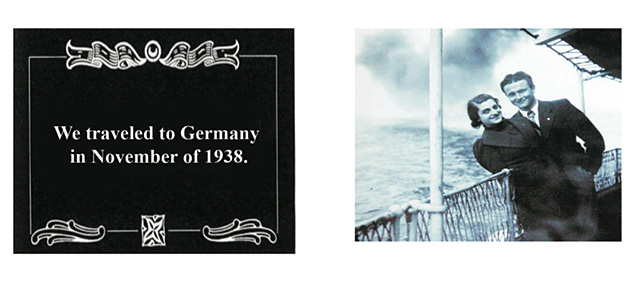

I did not look to women in my native country, but to women from my everyday life. One was my mother-in-law. She was a strong, educated, intelligent woman who was both kind and gentle but also determined and wise. Born during the Ottoman period, she became a chemical engineer in the Republic. I did a work titled Lost Suitcase, that re-told the stories that she told me. It was based on reality, but was really fiction. I chose to use a melodramatic romantic style often found in old Turkish films. It shows her determination to get an education and to marry a man of her choice from another clan, two people from two different minority groups.

One of my earlier videos Grandmother’s Lace researched the history of lace making among my mother in law’s elderly female relatives; designs of highly skilled masterpieces that ended up stored in trunks. The work was also about the suppression of identity and religion. It also included a male voice singing a secret Sebatay Levi prayer.

My recent addition to this series, My Name is Azade (Freedom), is about another woman who influenced me. The main character, Azade, was also born in the Ottoman period, but became a professional gymnastics teacher in the Republic. I took lessons from her from 1975 to 1980 when she was in her 70s and I not yet 30. Because of her, I continued all my life to exercise. She never became world famous, but she developed a unique system of teaching and a body of work that was very important. In the 1970s, she was incorporating yoga and pilates into her practice. When she left Turkey, she gave me a home movie of her performing her movements. I kept that video all these years and used it for my Passing On II video. From her video, I selected four movements and taught them to my daughter-in-laws, my granddaughters, my pilates teachers, and two other of her former students. My video project shot from above in a sense illustrates the process of passing on. We look for inspiration, make an effort to internalize this and find our own way of being, then we teach and pass on to others what we develop.

Tuğba: You often transform personal memories and objects from the past and family stories to use in your artworks. How do these intimate elements turn into the narratives that you share with other people and that anyone can relate to?

Nancy: That’s the whole purpose of turning something into artwork. You start from the personal, but transform it into something meaningful to others. For example, let’s look at my work People Objects (2003). Who gives objects value? Someone gives us a present. Every time we see that object we remember the giver. In this project, I photographed objects, digitally added the name of the person they remind me of and printed them on small pieces of Plexiglas. After the show, I gave the Plexiglas pieces to the original givers.

What is an artwork? An artwork seems to me to be a type of document, the documentation of a process, something that was thought or experienced. I wrote a short tautological text, “I am documenting the document. Someone is documenting my document. The documentation is being documented. My document, documentation, is our document. The document has been documented.” I recited this in front of a camera for a Sanatın Tanımı Topluluğu- STT (The Definition of Art Group) film in 1994 and then remade it for myself in 2012. An artwork is a document of an artist’s thought process while trying to understand. The artwork is the byproduct.

Tuğba: In works such as 1980 dated 2012, you refer to stories and realities of the past. Is there any significance of producing that work in this particular time? Why not earlier or later but that day?

Nancy: Some of my work includes memories but it also relates to current events—such as the work I made with scarves. I would not have thought of doing an artwork with scarves if they were not such an important contemporary symbol. I went through my husband’s family portraits from 1930s until 1980 to find photographs of female family members wearing some type of head covering that had no political or religious connotation. I remembered before 1980s when I uninhibitedly wore a scarf. I did work with scarves based on a memory before scarves became a political and a religious symbol. I did a research about scarves. How do you design a scarf? For example, they have a border but what should the border be? I took a trip to İznik to look at İznik tiles to see if there were any motifs that I could use. I transferred the photographs of women wearing scarves into black and white drawings for five silkscreen scarves. I also started reading articles about the history of the headscarf in Turkey. The sixth scarf is a very long scarf with a handwritten text based on this research. This scarf has several meters of empty white space because the story is continuing. This series would be an example of both using my personal history and also looking at current events.

“For me, the medium was no longer important; only the idea”

Tuğba: How did your artistic practice become interdisciplinary? Today we see more and more interdisciplinary practices in the art world, but 20 years ago this was new.

Nancy: Initially, I was a very traditional painter educated as an Abstract Expressionist in the United States. Until 1990, I made watercolors, acrylic paintings, collages, and expressionistic work and had had three solo exhibitions. For the entrance of the new Mövenpick Hotel in Istanbul, Sıdıka Atalay bought a series of collage pieces on wood. Unlike most artists who would immediately become very excited and happy about such a situation, I started questioning. What does it mean for my work to be bought by a hotel and to be in a hotel? Is being sold what gives artwork value?

Simultaneously a Fulbright scholar, Nan Freeman started teaching a class in 20th Century Art History at Boğaziçi University and I took her class. She really influenced me. I had been in Turkey for 20 years; we didn’t have Internet, new art books, or magazines. In her class, I realized how much I didn’t know or understand. For example, I did not understand conceptual art. I was about 40 years old when this wonderful and dynamic teacher exposed new ideas to me. Freeman saw my eagerness and when she left, she gave me all the books she brought with her. I read everything and realized, I really did not want to make paintings any more.

I started researching conceptual art, but it wasn’t easy because it wasn’t popular anywhere in the world and there was not a lot written about it. My sons were in university in the USA and I used their university’s libraries. I also visited the Castelli Gallery in New York that represented Joseph Kosuth.

After speaking with Prof. Zeynep İnankur at Mimar Sinan University, I decided to do a PhD on how conceptual art came to Turkey. While continuing to teach full-time at Robert College, I began classes at the university. For four years I read, wrote, and attended Şükrü Aysan’s STT (The Definition of Art Group) meetings. As a part of my research I also interviewed such artists as Füsun Onur, Ayşe Erkmen, Canan Beykal, Gülsün Karamustafa, Serhat Kiraz, Ahmet Öktem. After finishing my thesis in 1995, my art practice became interdisciplinary. I called my way of working “art as dialogue.”

Tuğba: During this great shift in your art practice, is it only the medium that changed or was it also concepts, ideas, themes?

Nancy: After finishing my research, I rejected painting as a method and realized I could use whatever I needed to materialize my ideas. I am not a photographer, but I started using photographs; I had not been trained in video technology, but I started making video works; when digital technology arrived I moved from using photocopies to making digital prints. For me, the medium was no longer important—only the idea. So that was a big shift.

Tuğba: In the 1990s, conceptual art was something very fresh in Turkey. The mid and late 1990s, was a very special period and conceptual art was on the rise. Do you think this change in your work was also related to the dynamics of that time?

Nancy: It was something I believed in. It was just the way I thought it should be. In the 1990s lots of people were thinking this way. I was working with a group of women artists, Gül Ilgaz, Neriman Polat, and Gülçin Aksoy. We shared a studio and strove to legitimize our way of working which was more language and idea based. We organized our own exhibitions and were always present to explain what we were doing. By 2000, we saw that we had succeeded in legitimizing our methods and invited other artists, some working with video and installations others were painters or sculptors, to work with us to organize three other exhibitions. Our aim was to destroy the polarization between painters and sculptors on one side and people using photography and video or installation on the other…

In the 90s many exhibitions used complicated philosophical titles that nobody understood. We wanted to emphasize more local topics and to have exhibitions that were dealing with what we were experiencing at that time. We organized three exhibitions, Yerli Malı (Local Produce), Yurttan Sesler (Voices from our Homeland) and Aileye Mahsus (For Families Only) dealing with local concepts. Our previous exhibitions had been about “being in between” because we were not painters or sculptors and our way of working hadn’t been totally legitimized.

In my opinion, a “significant” current trend in the contemporary art scene is the “art of social practice” or what I named “art as dialogue” in 1995—work that involves social interaction and focuses on current problems. I see collaboration as a very important way to work. I had always wanted to open a non-profit informal art space that supported projects dealing only with relationships, sharing and ideas. In 2007, when Hou Hanru chose the 1960s Istanbul Trader’s Market Shopping Center (İMÇ) as a venue for the Istanbul Biennial, I invited Adnan Yıldız to use shops I owned for a peripheral project. Volkan Aslan and I had been wanting to open an artist’s initiative and after the positive experience in this space during the biennial, with the help of Marcus Graf as our first curator we opened 5533.

Tuğba: How has your practice evolved after founding 5533?

Nancy: This is a very interesting question, but one that I have not thought about until now. Of course, we designed, participated in and contributed to different projects at 5533, but Volkan (Aslan) and I did not open this initiative to promote our own artwork and never thought of showing our work in this space. Nevertheless, I have always felt that 5533 completed and continued my practice because I see art as a space to create models for living, to try to understand the world we live in, to question, to discuss and to experiment. Since 5533 is about experience, discussion, meeting others interested in art and sharing ideas, it has undoubtedly enriched my practice even if I cannot tell you how, even if I cannot quantify or qualify. I can only say that I feel very lucky to have had the chance to work with the different local and international artists, curators, students, spectators and neighbors who have contributed to making 5533 what it is today.

Edited by Merve Ünsal

///

Working as an artist, teacher, art historian, and art critic, American born Turkish artist Nancy Atakan has been a resident of Istanbul since 1969. Her art work has been represented by Pi Artworks since 2009 where she has had four solo shows in Istanbul. With Volkan Aslan, she co-founded 5533 Artist Initiative in 2008. In 1998, her book Alternatives to Painting and Sculpture was published and a revised second edition came out in 2009. Atakan earned her PhD in art history from Mimar Sinan University, Istanbul, in 1995. She has taught in the art departments of Robert College and Boğazici University, Istanbul. Some selected exhibitions include: Sporting Chances (solo), Pi Artworks London, UK (2016); Small Faces, Big Bodies, Elgiz Museum of Contemporary Art, Istanbul, Turkey, (2015); Keeping on Keeping on, Treibsand Art Space on DVD, Zurich, Switzerland (2012); Dream and Reality- Modern and Contemporary Women Artists from Turkey, Istanbul Modern, Turkey (2011); Under My Feet I Want the World, Istanbul Next Wave, Akademie Der Kunste, Berlin, Germany (2009).

Tuğba Esen is the editor of culture and arts at Agos Newspaper. She is at the same time managing the press and public relations for the gallery Pi Artworks Istanbul/ London. Since 2013 she has been working in freelance projects. Nowadays she is writing her first book, biography of an actor, which is to be published by Aras Publishing in late 2016.