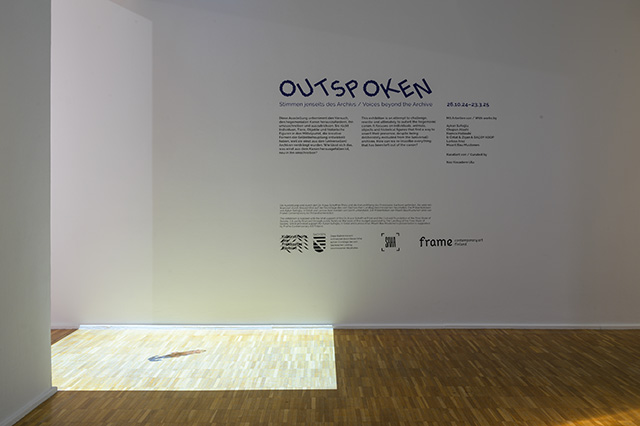

Language’s failure to hold us has never been as acute as it is today. In “Outspoken. Voices beyond the Archive” (Oct 2024–Mar 2025), an exhibition at the Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst Leipzig, curator Naz Kocadere Ulu conjured ghosts of the past and the future, languages unspoken, archives buried, through a constellation of works by artists Aykan Safoğlu, Chupan Atashi, Hamza Halloubi, İz Öztat & Zişan & BAÇOY KOOP, Larissa Araz, and Maarit Bau Mustonen. As the exhibition delves into what it means for artists to articulate today’s political, social, and cultural realities, a throughline emerges: the slippery nature of the scaffoldings we construct to make sense of our world. The oscillation across temporalities in the exhibition reflects an urgency; we don’t have the luxury to stay still in place or time. —Merve Ünsal

Merve Ünsal: I want to draw on the relationships between speaking, articulation, and artworks. What does speaking, or rather, outspeaking mean for you within the context of this exhibition?

Naz Kocadere Ulu: The pressing question “How do we perceive an artwork in the dark?” stood out the most and opened further while building the curatorial framework. Dissecting such a quest meant allowing a chance to re-diagnose what the “dark” signifies. What does darkness contain? Because I was working on developing the framework on a parallel timeframe of the attack on October 7, 2023, and the following war it led to in the Gaza Strip, darkness corresponded to catastrophe. I expanded my research on the following readings to trace linguistic systems and cultural belonging: The Library at Dark by Alberto Manguel + Alter ego : twenty confronting views on the European experience, Edited by Guido Snel + The Reluctant Narrator, Edited by Ana Teixeira Pinto These readings were accompanied with my interest in the postnational digital pavilion project DRIFT, that reflected on the entanglement between land, water, movement and m/otherlands. DRIFT-What is Nation

I gathered that the action of conveying information or expressing one’s thoughts and feelings in spoken language, or “speaking” in short, does not necessarily happen alongside the blockages of the unbreakable authority. For this reason, I felt the need to voice speculative thinking out loud in the company of these artworks. Speaking meant thinking out loud with various artistic positions.

As part of my personal experience in Leipzig, attending a multilingual choir group has been an incredibly satisfying engagement. Even though some do not speak the language (Greek, Turkish, Kurdish, Laz language, etc.) of the chosen song in practice, the community of people who live here in Leipzig take much joy in participating in this volunteer choir. I think being able to act upon an experience via any available sense, such as feeling one’s vocal cords and instinctually tuning with the surrounding vocal range, extends beyond one’s perception and the initial urge to comprehend everything. In my opinion, the physical impact of voicing even foreign words out of your system/mind creates an irreversible epiphany that makes imposed information redundant. It pushes the ignorance aside and widens perspectives on deciphering the truth about what it actually means to enforce diversity and inclusion.

So I believe that outspeaking not only meant being brave or bold enough to speak about matters that are being manipulated, blocked, and masked by the power structures, but also speaking out loud about culturally specific issues within an international scope with an open mind, with respect to the cultural communities and their histories.

Courtesy of the artist Hamza Halloubi and tegenboschvanvreden Gallery, Amsterdam.

MÜ: There is a paradigm shift as we move between historiographies, archives, institutions, and artworks—they deal in different languages. How do artworks intervene in these already-existing realms? What are some of the strategies that the artists use in the exhibition?

NKU: This paradigm shift reveals itself through the artworks that operate in portraying multiple personas, reviving haunted animals, highlighting alternative narratives through dismantling the Western Modernist readings, and substituting corporeality towards a textual or botanical entity. The artworks by İz Öztat, Maarit Bau Mustonen, Larissa Araz, Hamza Halloubi, and Chupan Atashi move between historiographies, archives, institutions, various entities, as well as different languages.

For instance, in her ongoing body of work, İz Öztat constructs the (auto)biography of Zişan (1894-1970), who appears to her as a historical figure, a ghost, and an alter ego. She responds to Zişan’s work to create a complex temporality that allows the suppressed past to intervene in the increasingly authoritarian present. İz employs abstraction and visual codes to touch upon the subjective personal stories we tend to neglect when reading violent histories. İz steers away from the language of diplomacy and international relations, instead cracks open what feels like an old chest that carries the intimate archives of a long lost friend, ally, “sister”, hence asks with a speculative approach: ‘What if Zişan were alive today?’

Another work on display by İz Öztat, in collaboration with Zişan, is titled Conductor. This installation presents a ritual object that could be “activated with breathing,” and thus introducing a metaphor of oral communication. The artist claims how the archival material like such can also appear in life, flesh, and breath, being brought to our contemporary times like a time machine. In order to better articulate Conductor, it’s wise to note that the Arabo-Persian script was used in the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey until 1928. The early 19th-century debate surrounding the language policy in the Ottoman Empire coincided with the founding of the Republic in Turkey, which was enforced via the lingual usage with a modernist approach. Therefore, it’s almost as if the nationalist implementations cut back the breathing capability of the script that required the necessary vowels to be able to voice it, as it’s a particular feature of the Arabo-Persian script, which was used in the Ottoman Empire and the early years of the Republic of Turkey.

Courtesy of the artist İz Öztat and Zilberman Gallery, Istanbul.

MÜ: Site-specificity and speculative historiographies also emerge as strategies in the exhibition.

NKU: Maarit Bau Mustonen’s site-specific installation Nudes’ carries the dust jackets of the books from the GfZK library to the front. Pointing towards the “bodies” inside the dust jackets, the title implies how the “nudes” are stripped from the cloak of information they are expected to carry or that they have chosen to go bare instead. On the other hand, the artist’s book titled Plural, documents the collective experience from a gathering of nine individuals, all named Maarit Mustonen, which was orchestrated by the artist in Helsinki. The realm of companionship under a shared namesake reminds the concept of nationhood and perhaps confronts one with the manipulated perspectives of it nowadays.

Whereas, Larissa Araz provides an alternative but darker perspective that tempts one to confront their past primitive roots via natural history literature. In her body of work, In Hoc Signo Vinces Araz departs from her survey of the final years of the Ottoman Empire to the establishment of the Republic of Turkey (1840-1923), where colonialist and imperialist scientists and missionaries traveled to the Ottoman territories to research the region’s geography, nature, and socio-political structure. The researchers discovered species in Anatolia and Mesopotamia that have not been recorded in Western scientific literature, and classified these findings as belonging to the animal class with Latin names such as Vulpes Vulpes Kurdistanica (Satunin, 1906), Ovis Armeniana (Blyth, 1840), and Capreolus Capreolus Armenius (Blackler, 1919). The artist stimulated the confrontation to explore the reasoning behind the removal of the words “Armenia(n)” and “Kurdistan” from the taxonomic names of three endangered animal species (roe, wild sheep, and fox) by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Turkey in 2005. Replaced with the words ‘Anatolian’ and ‘Eastern’ instead, the Ministry declared that the original names were “divisive and contrary to Turkish unity.”

Larissa repeats the act of classifying in Latin and mimics the visual codes that remind one of the literacy to detect a hunting scene. She mimics the environment in nature, where one can not decide whether they are the hunter or the prey. She encourages the visitor to look into their stance when approaching a “territory” or a “community” that necessitates authority and/or hierarchy.

6 C-Prints, each 70 × 70 cm.

(Right) Chupan Atashi, Flowers, 2010. Photo series, 6 C-Prints, each 34 × 34 cm.

Courtesy of the artist Chupan Atashi

MÜ: Figures from the past, real or speculative, emerge as interlocutors in the exhibition. And photography and its indexical claim appears as a throughline as we begin to question which representation or presentation is of what moment or place in time.

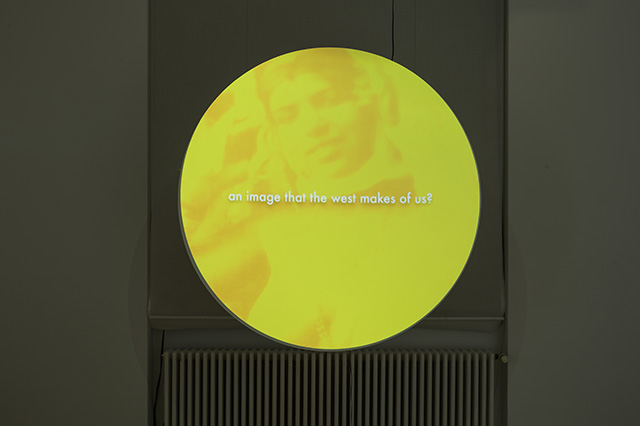

NKU: The video work Writing Back by Hamza Halloubi is an attempt to paint a portrait of Cherifa, an enigmatic Moroccan woman who lived in Tangiers in the 1960s. Exotified in the writings of Jane and Paul Bowles and William S. Burroughs who fetishized this woman’s illiterateness, the video addresses shadow and silence as strategies for deflecting the orientalist gaze.

The work confronts one’s notion of writing on someone who might not have the capacity to respond nor read—whether it’s due to their being illiterate or dead or alive. It touches upon the sensitive topic of taking the responsibility to express judgment about someone or a community without them having access to confirm or agree on what is being written/told about them. Hence, the problematic essence of Orientalism, has become even more appalling today regarding the manipulation of news flow in the Middle East.

Instead of depicting this female figure directly through an outsider’s gaze, Hamza expands the space/canvas and uses silhouettes, voices, and facial elements in moving images to describe her. I see this gesture as an attempt to push forward a new format of expression. Hamza refrains from using the traditional approach of portrayal, and criticizes the Anglo-Saxon authors who use a downgrading and unjust rhetoric when writing about the subject. Instead, Hamza articulates a set of visual codes, such as the speaking mouth, the flashing text, and the veil that (later) uncloaks from the Western gaze that reduces Cherifa into a caricature.

The furthermost part of the work, one hears a male voice speaking in French without any subtitles, presenting limited access for non-French speakers, which I take as an implicit intention to highlight the situation of being lingually disconnected. Later on, I found out from the artist that the voice belonged to Gilles Deleuze, which he reads The noise of time : the prose of Osip Mandelstam, translated with critical essays by Clarence Brown (1986). The excerpt reads: ‘My desire is not to speak about myself but to track down the age, the noise, and the germination of time. My memory is inimical to all that is personal. If it depended on me, I should only make a wry face in remembering the past.(…)’ (p. 113/260) I believe that the statement of ‘one’s memory standing against everything subjective’ is presented as the better alternative for depicting Cherifa. As the excerpt scrutinizes, the non-objective view summons prejudgment and does not provide a just description nor respect to any subject.

Chupan Atashi’s photo-series titled Tehran’s Self-Portraits consist of the documentation of themselves as urban pedestrians within Tehran’s cityscapes and monuments. Taken with a pinhole camera with flash lighting as the artist walks through the streets of Tehran, the project coincided with the so-called Green Movement, a wave of civil uprising that took place in the city during Iran’s controversial presidential election in 2009. The Green Movement designated a pivotal significance in Iran, as the first image-based movement of its kind, due to the increasing use of smartphones and the internet. The ability to capture and circulate images allowed this technological development to raise the important challenge to government censorship, which led the way to the authorities to become cautious about the act of taking photographs. Considering the position and agency of Atashi within this historical background, the national, personal, and political narrative clash together. Depicting themselves as fragmented by the oppressive mechanisms of control and censorship, Atashi was captured by the city’s surveillance cameras and imprisoned for the crime of documenting their presence on the streets. The statement of the interrogators declared that the artist was allowed to continue photographing if they agreed to refrain from depicting themself whilst encouraging them to depict flowers instead.

With a similar prominent use of flash lighting as in Tehran’s Self-Portraits, the artist Chupan Atashi captures flowers located on the hill of Evin prison, where they were being held. These wildflowers have not been deliberately cultivated, but grow naturally in harsh conditions in desolate areas. The depiction of the wild flowers reveals them as strong metaphors to redirect the viewer’s attention from violence and oppression, whilst covering it in aesthetics.

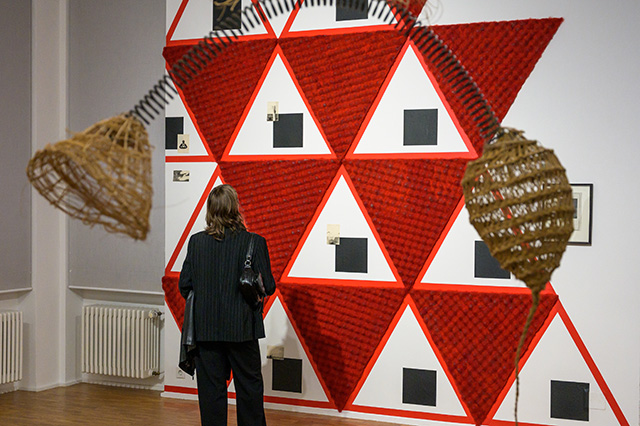

(Foreground) İz Öztat, Circle of Eternal Return (After Zişan), 2013 / From the series Posthumous Production. Vegetable fibers, spring, thread, 120 × 80 × 80 cm.

Courtesy of the artist İz Öztat and Zilberman Gallery, Istanbul.

MÜ: The state of being haunted appears across different works. In particular, what are the kinships imagined through the state of being haunted?

NKU: The state of being haunted appears across various works, in particular via the works by İz Öztat, and Hamza Halloubi. I would like to expand the notion of haunting further through my readings on Dr. Ana Teixeira Pinto’s seminar titled Ghost Stories. In her talk, she references Avery Gordon’ writings on describing a ghost as: “not simply a dead person, but the form by which something that was lost makes itself known or apparent to us, even if fleetingly or in a barely visible manner.” She explains Gordon’s arguments and adds that “by way of this haunting, (a ghost) demands reparation, justice or at least a response.” With this in mind, one can interpret the collaboration between İz Öztat and the ghost Zişan, and Hamza Halloubi’s attempt to depict a fair image of Cherifa.

When Halloubi comes across the description of Cherifa through the writings of the Anglo-Saxon authors, he is disturbed and haunted by the false and unjust approach of her. The first sentences of the work ‘Writing Back’ begins with quotes of Paul Bowles and William S. Burroughs about their stay in Tangiers. Both Anglo-Saxon writers explain how (Tangiers) ‘this city was the set for orientalist stories where Moroccans was just part of the decor and not masters of their domain.’ Following the intro, the ghostly figure of Cherifa covered in a dark cloak walks around the streets of Tangier and haunts the artist through her unjust way of depiction within these Anglo-Saxon authors’ writings as ‘a ghost’ as well as an ‘ illiterate and veiled, poor, and lesbian. Halloubi continues this statement by adding: ‘The perfect character to represent the oriental, the evil one and the sorcerer.’ The artwork becomes an ode to Cherifa on what she would write back regarding how she has been described within the writings on Tangiers.

On the other hand, İz Öztat inhabits a mutual tongue together with Zişan, who appears to her as a historical figure, a ghost, and an alter ego. Zişan’s revelation to İz started as a ghost. Following her dream, İz heard Zişan’s voice as a spirit through a portal and later was able to hear, tune in, and respond to Zişan. Born of an affair between Nezihe Hanım, a teacher from an upper-class Turkish family and Dikran Bey, an Armenian photographer, Zişan’s destiny was marked by an ambiguous belonging from the outset. She fled Istanbul with her father in 1915 to escape the Armenian Genocide and meandered through the canon of avant-garde art without ever being noticed. Her archive consists of text, sketches, photographs, photo-montages and objects. Zişan did not identify as an artist during her lifetime. She produced with pseudonyms and/or anonymously. Therefore only now İz situates her archive within an artistic context. İz takes on Zişan’s archive and interpret them through her practice in order to enable and suppress past to intervene in the increasingly authoritarian present.

Within the context of İz Öztat and Zişan’s practice, I think that the act of haunting corresponds to the notion of confronting with the reality of violent histories. As Ana Teixeira Pinto explains in her talk (Why words now), the phantom returns from the past in order to reveal something hidden or forgotten or to deliver a warning. Considering the appearance of Zişan came about within a dream of İz Öztat, she revealed herself when one can not flee, but is captured by confrontation of reality. As haunting is deeply embedded within the discourse of loss and mourning, and closely connected with the field of trauma studies, bringing back a figure who outlived a catastrophic history becomes a strong attempt to respect and cope.

Rewinding back to the period which inspired the revival of Zişan within İz Öztat’s artistic practice, I’d discuss the portrait titled Sisters (After Claude Cahun) (2003). The work depicts two faces that appear to belong to another time, also reflecting an uncanny resemblance to one other. Portraying the artist İz Öztat with Claude Cahun in a ghostly aesthetic, the work is a reinterpretation of a self-portrait by Claude Cahun, the French surrealist photographer, writer, and self-portraitist, who challenged strict gender roles of her time as well as actively contributed to the leftist movement of communist writers during the World War II. This early work by Öztat reflects her interest in multiplicity of the selves and intergenerational dialogues.

Öztat revisits Que me veux-tu? (1928) by Claude Cahun, a self-portrait produced by double exposure. In making Sisters, Öztat replaces one of Cahun’s images with herself, suggesting both identification and a close dialogue with Cahun. Öztat’s close engagement with Claude Cahun’s work, which has been researched and theorised after the 1990s as a precursor of performative gender theories, informed the emergence of Zişan (1894-1970), who appears to her as a historical figure, a ghost, and an alter ego.

Zişan – İz Öztat – Claude Cahun figures can be read as profiles that are bold enough to speak the truth that safeguards the right of each individual. It’s no secret that being in Germany throughout such discussions have been particularly difficult, thus the censorship mechanisms hit quite hard and are becoming even more destructively punitive every day as we speak.

Preserving one’s stance, a sisterhood can provide a network of support and encourage shared experiences to empower each other to overcome challenges. Sticking together can stand against patriarchal norms, promote an equitable society. By standing in unison, the collective can reflect strength and determination. On the other hand, as the global protests against oppressive governments rise today, especially in Turkey, Serbia, South Korea, among others, the aftermath of these riots often harms those who were forcibly ripped out of their collective structures. Not everyone can afford to take the risk of being taken into custody for speaking up their truth, or being fired from their job for opposing to the authority, or being cut from the financial grant mechanisms for standing against the colonial governmental mechanisms. Bringing forward the inescapable topic of auto-censorship to tackle such hardships, the publics are now looking for sustainable ways to boycott, claim opposition, preserve unity, and build solidarity among each other to create a system of meaningful governance.

Courtesy of the artist Larissa Araz and Versus Art Project, Istanbul.

(Right) Hamza Halloubi, Writing Back, 2019–2021. Single channel video projection, color, sound, 7’22”.

Courtesy of the artist Hamza Halloubi and tegenboschvanvreden Gallery, Amsterdam.

MÜ: “Outspoken” is an exhibition that relates and narrates practices of articulation in different forms across times and places. How did “Outspoken” change your practice?

NKU: The exhibition shifted my practice to be bold and clear about my stance in political matters, which I believe cannot be kept away from the contemporary art field. Having the courage to speak up for your truth is not always easy, especially when doing so can disrupt one’s livelihood. Particularly whilst one is familiar with the auto censorship and delicate censorship mechanisms that comes naturally in delivering political artistic practice in Turkey, but still, unpleasantly surprised when facing or hearing any kind of Palestinian presence in the public sphere, the crude forms of censorship are present in most of Europe, and especially in Germany.

Nonetheless, I often found myself questioning if it is fair and/or productive to put such idealistic projections on the impact of contemporary art today. Considering the immense pressure (financial, social and political marginalization) one faces when expressing their political stance or views via arts and culture in Germany (including, but not limited to many other countries in the EU and all around the globe), I increasingly felt that our (arts&culture workers including artists, curators, researchers, academicians, etc.) attempts to present meaningful art programs to be redundant. By meaningful, I mean a timely and reasonable framework that could provide guidance for further questioning to grasp and tackle the socio-political predicaments of our time. Keeping in mind that, in my opinion, the contemporary should trace the current times with valuable observation and a constructive roadmap that could spark new methods of exhibition making.

Surely, exploring the paradoxes between art and social change, belief and technology, lived experience and institutional infrastructure could work as a driving force for some, but not for me— anymore. Instead, it is pushing me to detach from the niche artistic thinking pattern that has the tendency to be short-sighted to avoid meddling in challenging times like today.

MÜ: Which direction do you find yourself going in?

NKU: I’m leaning towards training myself to measure the essential impact of arts and culture. I feel the need to clearly define the impact of arts and culture as vital to find a grounded reasoning for my practice. My thinking behind this judgment is derived from witnessing the substantial changes (the rise of enforcement of anti-migration laws, budget cuts in the cultural field, drastic reduction of English-taught programmes in the academic field, censorship against anti-colonial and Pro-Palestinian voices, etc.) in the cultural policy in Germany following the rise of the AfD, the far-right political party in Germany. Coming from a country where the funding for arts and culture is not widely supported by the state, but rather by private foundations, associations, and banks, the field workers have always found their way within the small ecosystem to survive against all odds. However, as governmental structures got even more restrictive against its public, the consequences of resisting deteriorated to the state of collapse of free expression.

In such formidable setting, I came to realize that developing agile communication strategies and cooperative mediation methodologies is more abundant. I think that directing/investing the majority of attention in building a magically inspiring curatorial framework appears to be pointless, given the circumstances that ache for an impactful message that can ease the burden of our heavy agenda. Looking back at my experience at an institutional structure located in an unfamiliar ((East) German) culture, I came to realize that no matter the framework a curator builds, one inevitably bumps into the limitations of nationwide cultural policies, marginalisation of subjective narratives, conviction of the century old orientalist reading habits and extremist political tendencies of that particular period and/or global financial discrepancies.

Courtesy of the artist Hamza Halloubi and tegenboschvanvreden Gallery, Amsterdam.

Naz Kocadere Ulu works as an arts manager, curator and writer. With a keen eye on the ever-changing structure of language, Naz focuses on its relationship with identity, cultural belonging, representation, gender and authority. With a background in visual communication design, Naz received her master’s degree in cultural management. During her graduate studies, Naz focused on the strategies of audience development at SALT Istanbul and Kunstinstituut Melly Rotterdam. Later, she attended the Curatorial Program at de Appel Amsterdam with the support of the SAHA Association. Since 2013, Naz has realized a series of publications, exhibitions and research programs in various art galleries and institutions, including SALT in collaboration with the platform Asociación de Arte Útil and the 13th Istanbul Biennial. Recently, as part of her curatorial fellowship supported by the Cultural Foundation of Saxony(KdFS), she curated the group exhibition Outspoken Voices beyond the Archive at Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst (GfZK) in Leipzig, Germany.

Her latest curatorial projects include multifaceted publication “What are the words you do not have yet?” supported by Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst (AFK), and the group exhibition All water falls into language supported by the Consulate General of the Netherlands in Istanbul. Her writing has previously appeared in Sanat Dünyamız, Art Unlimited, Argonotlar, Borusan Contemporary Blog and SALT Online Blog. Naz is a member of the International Association of Art Critics, AICA Turkey.

//

All installation views from Outspoken: Voices Beyond the Archive exhibition; Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst Leipzig, Germany. Photographed by Alexandra Ivanciu.